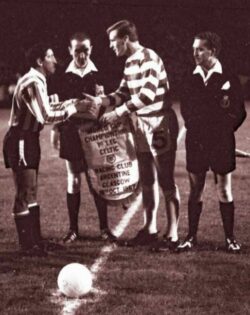

Billy McNeil and Racing Club captain Oscar Martin at Hampden Park on 18 October 1967. From Celtic In The Black And White Era published by DC Thomson.

“There’s only four of us left now.”

John Clark is in a wistful mood as he casts an eye over the famous team photo that hangs in the reception area of Celtic Park. Just a few steps further inside is the reason why – a handsomely arranged tribute to Clark’s friend and fellow Lisbon Lion, Bertie Auld, who has recently passed away. As we settle into a room that adjoins the boardroom, it is clear to see that Clark misses Auld. Outside the window, the tributes to one of Celtic’s best midfielders and finest raconteurs continue to accumulate as club staff, wrapped up against the autumn cold, discuss strategies to cope with the crowds that will flock to Celtic Park for the funeral that Friday, when Auld passes by Paradise one last time.

Clark picks out a spot in the middle distance. “When Bertie came to a game, honestly, it would take him 40 minutes to get from there to the front door. He had a word for everybody – a different story for everyone. He was very witty, a right Glasgow guy. But underneath it, he had a determination; he was strong. They were all strong.”

It was that steeliness Clark and his teammates had drawn upon after going behind after just seven minutes in the heat of Lisbon, before eventually breaking down Inter Milan’s methodical, massed defence to become European champions. Five months later, that resolve would be stretched to breaking point and beyond, as Celtic attempted to become the de facto world champions by winning the Intercontinental Cup.

What became a notorious trilogy of games would begin tetchily at Hampden Park before passing bloodily through Buenos Aires and eventually decided amid complete chaos in Montevideo. The boys that returned from Lisbon to open-top bus parades and universal acclaim would return from South America to disciplinary action and widespread condemnation – with even Michael Parkinson adding to the scorn. There were ramifications at the highest levels as well, with events on the field in South America leading to a surreptitious editing of a New Year Honours list.

Celtic 1 Racing 0, Hampden Park, Glasgow, 18 October 1967

“Two-and-a half-years ago Celtic were just another team and apparently content to be so. But with the appointment of Mr J. Stein as manager came the transformation. Parochialism gave way to complete and utter dedication to become the world’s best, and with their win in Lisbon, they now stand just one step away from the realisation of that aim. All that remains to be conquered is South America.”

Glyn Edwards’ words in the Glasgow Herald on the morning of the opening game of the 1967 Intercontinental Cup left little doubt as to the prestige the competition held at the time. The names that had lifted the trophy to that point were legendary. A Real Madrid side featuring Ferenc Puskás and Alfredo Di Stéfano had won the first edition in 1960. Pelé’s Santos had drawn colossal crowds to the Maracana as they won back-to-back titles before Sandro Mazzola’s Inter Milan did likewise. Eusebio and Benfica had two unsuccessful tilts. For a gang of twenty-somethings from the west of Scotland, this was undoubtedly a big deal.

Celtic’s opponents were Racing Club, from the Avellaneda district of Buenos Aires, who had won the Copa Libertadores by beating Uruguay’s Nacional over three tight games. Like Celtic, Racing were also first-time continental champions which meant, in an era where information was much harder to obtain, the two sides knew very little about each other. According to Clark, this was something that didn’t concern Celtic too much. “Big Jock wouldn’t be too worried about how they played. It was how we played which was his main objective in football, not the opposition.”

Celtic did though take the initiative of inviting the reigning world champions to Celtic Park to gain experience of playing South American opposition. A crowd of 56,000 watched Uruguay’s superb Peñarol side given all sorts of problems by Celtic’s pace and relentless attacking. Both sides were applauded generously off the field after a hugely encouraging 2-1 win for Celtic. Racing’s thirst for knowledge on their opponents was a good deal keener. Manager Juan José Pizzuti wrote to European-based Argentines, including Di Stefano, for any intelligence they could pass on.

The name’s Bond

Remarkably, Racing were then lent a hand by the most well-known secret agent of them all. On the last leg of the tiring journey from Buenos Aires to Glasgow, the weary squad was sparked to life as into the departure lounge at Heathrow strode Sean Connery, the current James Bond. The players instantly recognised one of the world’s most famous faces and swarmed Connery for handshakes and autographs. Pizzuti spied an opportunity and scrambled around the terminal, looking for someone who could speak both Spanish and English.

Soon an air stewardess was dutifully sat between the two men as Pizzuti drilled Connery for information on Celtic. Agent 007’s dossier was illuminating: detailing winger Jimmy Johnstone’s as Celtic’s main threat and left-back Tommy Gemmell’s ability to cut infield and shoot powerfully on his right foot. Connery was a confirmed Celt at the time, but he had gotten along so well with the Racing squad that he visited them again just before kick-off. As nerves jangled in the away dressing room at Hampden, the door swung open and in walked Connery, wishing the team good luck.

Across the corridor, Celtic were planning on making their customary fast start, but Clark recalls Stein adding one note of caution. “Big Jock told us we would find it different from playing in a typical European tie. He told us to be ready for something we’d never experienced before in terms of aggression. They’ll knock you down, shove you, slap you.”

As the game got underway in front of a crowd of 90,000, it seemed that Racing had heeded Connery’s warnings about Johnstone, who became the main target of tactical fouling. Early in the second half, a particularly egregious hack sparked a mass confrontation between the players and even drew Stein on to the pitch in protest. Johnstone’s treatment would be a feature of the three games. “That wee man was just like a ball to them,” Clark sighs. Racing finally cracked with 20 minutes to play, Billy McNeill’s looping header from a corner settling the game. The bad blood building between the sides was evident as McNeill prioritised aiming some choice words at his marker, Alfio Basile, over celebrating with teammates.

Cesar would let you know

Some saw that as out of character for McNeill, but Clark knew his centre-back partner and roommate wasn’t hesitant when circumstances required: “Aye – he’d let you know. He wasn’t shy in giving it out when it was needed, and you could understand it. These guys had ability – they had no need to approach the game the way they had.” There were further incidents as the game drew to its conclusion. Goalkeeper Ronnie Simpson was kicked while awaiting a corner, while Auld received a reverse head-butt, provoking yet another skirmish between the sides.

The win left Celtic needing to avoid defeat in Buenos Aires a fortnight later to claim the trophy. The rather strange format meant that the margin of victory was not factored into the two-legged tie with away goals also an irrelevance. That meant that one team could lose one game narrowly, win the other handsomely, but a play-off at a neutral venue would still be required. So likely was it that a play-off would be necessary that the venue and date were arranged in advance.

A break for international games gave Celtic some time for the bumps and bruises to heal before they resumed domestic action against Motherwell and a League Cup Final against Dundee. Celtic returned to Hampden with their suitcases packed and quickly went 2-0 up in the first 10 minutes of the game. Thoughts of cruising to a nice leg-stretching, warm-up win were dispelled when Dundee climbed off the canvas and set up a frantic finish in which five goals were scored in the last 17 minutes. “It was obvious that there will have to be considerable tightening up if the club are to return victorious from Argentina,” warned the Glasgow Herald’s match report after the 5-3 win.

From Hampden, it was straight to the airport where the travelling party left Glasgow’s biting autumn behind, landing 20 hours later in the late-spring heat of Buenos Aires. When they arrived at the fashionable Hindú Club north-west of the city, Stein sent the squad directly to bed.

Racing 2 Celtic 1, El Cilindro, Buenos Aires, 1 November 1967

If travelling to the other side of the world in search of a trophy was an intimidating and exhausting prospect, Clark couldn’t have chosen a better group with whom to do it. “We all got on well with each other; we were very close. They all had a good personality; you could be in anyone’s company on any day. There were never any cliques, nothing like that.”

The squad had other company as they settled into their new surroundings. Even on leisurely strolls around the Hindú Club’s lush rugby fields and manicured golf courses, the players were always accompanied by at least one police officer. “That was something none of us had experienced before. You couldn’t go for a walk yourself, only groups of three or four, and there was always a guy with a gun or something with us.” The police were on board the team bus on match-day as they departed their quiet surroundings and weaved through the city. “It was very warm, and we were heading through the town, and someone opened a window. A policeman stood up and told us it was too dangerous to have it open, making a sort of machete motion. It was quickly shut.”

The 70,000 inside El Cilindro ensured the stadium was rocking as Celtic made final preparations in the away dressing room. There was little chance of a local celebrity walking through the changing room door to wish them well as had happened to Racing in Glasgow. Indeed, when the time came to file out through the tunnel and on to the pitch, the door wouldn’t open at all. “We couldn’t get out,” remembers Clark, “There was somebody at it – the caretaker or whoever was in charge of the keys. So, the crowd are going off their heads, thinking we’re doing it deliberately.”

The door was eventually unlocked, but worse was to come seconds before kick-off. “We were loosening off and the next thing, Ronnie goes down. We didn’t realise how serious it was as we were all doing our own thing, but then someone says he’s been hit by a metal bar.” Simpson had to be replaced in goal by John Fallon. Argentinian interpretations over the years have tended to play the incident down, the missile usually referred to as a coin and the damage to Simpson as superficial. But Clark believes Simpson would have been very reluctant to make way. “Ronnie wouldn’t have wanted to miss that game, but he wasn’t even fit enough to play in the next match either.”

Bizarre scenes

Despite the disruption, Celtic made a strong start and won a penalty after 22 minutes when Johnstone forced an error in the Racing defence and was dragged down by goalkeeper Agustín Cejas. This sparked the curious sight of dozens of photographers making their way across the entire length of the pitch to crouch behind the goal before Gemmell could take the kick, with some seemingly more intent on distracting Gemmell than performing their journalistic duties. Gemmell’s strike was poorly directed but had enough power to trickle over the line after Cejas had got two hands to the ball. The Argentinian broadcast of the game then contained a bizarre interlude as the main commentator — reminiscent of the shopkeeper in Mr Ben — as if by magic, appeared on the pitch alongside the dejected Cejas to interview him about the kick live on air. Cejas’ replies were polite but curt.

The photographers made their way back to their previous posts and soon had the images they craved for as Racing equalised just 11 minutes later. Midfielder Norberto Raffo found himself in a huge amount of space behind Clark and McNeill and headed Humberto Maschio’s cross over Fallon. McNeill was always unwavering that the goal was offside, and his centre-back partner remains equally adamant. “The guy’s standing on his tod. He was offside. We knew – it was just a fact.”

Racing took the lead early in the second half. Juan Carlos Cárdenas was played in and struck a left-foot finish low across Fallon and into the bottom corner of the net. The goal sparked pandemonium and a further invasion of photographers eager to capture the celebration. After that, “the steam appeared to go out of the Celtic attack,” reported the Glasgow Herald. “The Argentinians slowed the pace, and their well-marshalled defence had little trouble keeping out the Scots.”

The game drew to its conclusion in a relatively uneventful manner, partly thanks to the Uruguayan referee, who drew praise for his control of the match from neutrals and the Celtic camp. With one win each, the tie was due to be settled in Montevideo three days later, but at board level, Celtic were giving serious consideration to going straight home. In the immediate aftermath of the game, Stein was striking a similarly exasperated tone: “We don’t want to go to Montevideo or anywhere else in South America for a third game. But we know we have to.”

After the two sides made the short trip across the Río de la Plata to Montevideo, Stein’s competitive nature returned to the fore. While the board were still reluctant, Stein had become ever more determined, as his comments to the press on the eve of the game made plain: “We want to win the title, not so much for ourselves but to prevent Racing from becoming champions.” Ominously, Stein added his players would not go looking for trouble on the field but that the players would “give as much as they are forced to take.”

Racing 1 Celtic 0, Estadio Centenario, Montevideo, 4 November 1967

Moments before kick-off in the iconic Estadio Centenario, a white dove landed in the Racing goalmouth. A photograph in the Argentine football magazine El Gráfico captured the Racing goalkeeper Cejas bending down to offer a gloved hand to the bird. “This wasn’t to be a prediction of events to come but more of a grotesque contradiction,” the caption read. Indeed, the first foul arrived just two seconds into the game, and it was soon evident that the Paraguayan referee, Rodolfo Pérez Osorio, was out of his depth. After 23 fractious minutes, he called the two captains together to warn them that if things did not improve, he would start sending players off.

Barely 10 minutes later, the game exploded with Clark at the centre of things. Johnstone was crudely chopped down by Juan Carlos Rulli, who ran away from the incident and the referee. Clark charged some 30 yards after Rulli, spectacularly squaring up to him and then Basile – both fists raised – in a style that would grace a 19th-century boxing manual. “It was like John L Sullivan, wasn’t it?” Clark says with a laugh, invoking the image of boxing’s first ever superstar. Mayhem engulfed the pitch as Basile was sent off for his part in the argument. His reluctance to leave the field and the haranguing of the referee drew more than a dozen white-helmeted riot police on to the pitch, batons drawn. Mystifyingly, the next to be sent off was Bobby Lennox, who had nothing to do with the incident.

Some put the dismissal down as mistaken identity, with Lennox confused with Clark. Other accounts suggested that the referee had previously nominated Basile and Lennox as the players he would send off if the captains could not control their players. Lennox’s departure was interrupted by his own manager as Stein ordered him to go back on the field. When the referee spotted Lennox had returned, he again told him to leave. But again, Stein pushed his man back on. The farce was ended when a policeman drew a sword, and Lennox decided it was in his best interests to leave.

Just after half-time Celtic lost their main attacking threat when Johnstone finally snapped. As he attempted to spin into space, he was dragged back by the Racing captain Oscar Martín, whom Johnstone punched twice in plain view of the officials. Minutes later came the moment that won the title and etched ‘El Chango’ Cárdenas’ name into Argentine football lore. With the ball bobbling on the threadbare pitch some 30 yards from goal, Cárdenas struck a left-footed drive that swerved unstoppably in the top left-hand corner of Fallon’s goal. “It was a screamer of a shot to win any game,” says Clark.

With the title seemingly gone, Celtic’s loss of control continued as they shed two more players in increasingly bizarre circumstances. As Cejas received a back-pass, John Hughes ran forward to hurry the goalkeeper into picking the ball up. As he did so, Hughes aimed a powerful punch at Cejas’ kidneys and then kicked him as he fell to the ground for good measure. Hughes’ explanation that he simply thought that somehow nobody would see him was testament to how far Celtic heads had gone.

A boot to the balls

The game ended in complete shambles as Auld reacted violently to a foul and became the fourth Celtic player to be ordered off. Auld refused to go, claiming to not understand the referee. Amid the commotion, Gemmell spotted a chance to settle another feud, creeping up to boot Humberto Maschio in the balls directly behind the back of the referee. Gemmell fled the scene as riot police arrived on the field once again. The final whistle drew dozens of people onto the pitch but no further retributions from either side. Indeed, the image in the foreground of the main TV camera saw McNeill and Roberto Perfumo exchanging shirts and embracing. Perfumo later claimed McNeill congratulated him in perfect Spanish. “The pressure of the game, once it stopped, that was it. There was no point fighting after that. The aggression just went out of it once the 90 minutes was up,” Clark recalls.

If McNeill’s gesture was a sign that ire was finally cooling amongst the players, off the field, the recriminations were only just beginning. Celtic chairman Robert Kelly described the game as “an ugly and brutal match containing no football”, promising to hold a “thorough probe” into events. Missives condemning the Celtic players for their lack of self-control were dispatched to Glasgow and London by the travelling press corps. An editorial in the Glasgow Herald lamented the game as “no more than an unseemly and sickening brawl,” adding that: “It was of course rash of Mr Stein to announce before the game that his players would give as much as they were forced to take.” The squad had little choice but to accept the criticism, but the irony of an incident where two prominent travelling journalists lost their own self-restraint on the journey home was not lost on Clark.

“We were in this wee private lounge, and everyone was just sitting about waiting for the plane, then suddenly tables and chairs go flying and two of the press guys are standing up to fight each other. And they’d been lambasting us in their newspaper reports!”

Highlights of the game, broadcast on BBC1 two days after the match, shocked the general public and drew wider opprobrium. Even Michael Parkinson criticised the players in a discussion on his daily programme Twenty-Four Hours. The Celtic board took the unprecedented step of fining every Celtic player £250. Clark and the players were not best pleased: “That was a lot of money to people back then. We were only on about £60 a week at the time. But I couldn’t swear to you we definitely paid it.”

Remarkably the most resistance to the fines came from Argentina. Baldomero Pico, the Racing president, feeling magnanimous in victory, sent a letter of appeal to his Celtic counterparts declaring the violence to be far away from the usual standards of both clubs. “It was sad that two teams as good as this should have had such a bad day.”

Valentin Súarez, the director of the Argentine Football Association, declared that it was the Celtic board that should be fined and not the players. While most of the aftermath played out noisily in public, it was in the quiet channels of government communication that the most dramatic repercussions were secretly taking place. A 2007 release of government documents revealed that events in Montevideo had led to Stein’s name being discreetly taken off the list of those to be honoured in the 1968 New Year Honours list.

Sir Jock?

The knighthood awarded to Matt Busby at the first opportunity after Manchester United’s European Cup win the following season provoked complaints in Scotland and sparked a wave of correspondence between Whitehall and Edinburgh. A letter from the Scottish Executive to the influential civil servant Sir John Lang shortly after Busby’s award bemoaned the timing of Celtic’s European Cup win. “The most infuriating aspect of the matter is that, had we attempted the almost impossible feat of getting an honour for Celtic in the Birthday List some 10 days after the European Cup, the subsequent events in South America which upset the applecart would have come too late to have any effect.”

In the spring of 1970, when Celtic had again reached the European Cup Final, the Scottish Office sought to position Stein for an honour once more, this time in a letter direct to the prime minister, Harold Wilson. “There is a good deal of dissatisfaction in Scotland over what is regarded as an undue proportion of honours for professional football going south of the border. When Celtic became the first British team to win the European Cup in 1967, we failed to recognise this by an honour for Stein. His name was I understand removed from the New Year list at a late stage because of the unfortunate events in South America, when as holders of the European Cup, Celtic played an Argentine team in a match marred by misbehaviour on the field.”

Stein was eventually given a CBE, but the failure to award him a knighthood has long irked many, including Clark. “To this day, I think Jock Stein should have been knighted. Look at what he did. There are others – good luck to them – that got it, but Jock deserved to get it along with them.”

Despite everything, Clark harbours few regrets about what happened during those epic three games. “I don’t think the players would’ve given it a thought if we had to play a fourth game out there. Through it all, the only thing you’d

change was our discipline. But that has to come from the referee – if he’d done his job and protected the players, it would have been a different game. There was no need for what Wee Jimmy went through at times. The guys that have passed away and the ones that are left, they’d all say the same, they’d all agree.

“You wouldn’t change your life for all that. That’s history, that’s part of the story of the Lisbon Lions. We were there. We did our best. It didn’t work out. And I’ll tell you: I wouldn’t change one player in that team.”